In response to a student who has left the Dhamma and training who is disparaging the Buddha's states as merely human and his teaching as worked out through his own intuition, the Buddha shares his states and abilities to Sāriputta. This teaching captures his words on the four confidences, the eight assemblies, the four types of birth and the five destinations and Nibbāna.

Four Confidences

These are the four confidences, Sāriputta, by which the Tathāgata, endowed with them, claims the noble place, roars the lion's roar in assemblies, and sets in motion the spiritual teaching. Which four?

If someone were to claim that these phenomena are not completely realized by the Perfectly Awakened One, I do not see anyone in the world — whether ascetic, brahmin, deva (deity), Māra, Brahmā, or anyone else — who could rightly refute me. Not seeing this possibility, Sāriputta, I dwell having attained security, fearlessness, and confidence.

If someone were to claim that the taints of one whose taints are destroyed are not destroyed, I do not see anyone in the world — whether ascetic, brahmin, deva, Māra, Brahmā, or anyone else — who could rightly refute me. Not seeing this possibility, Sāriputta, I dwell having attained security, fearlessness, and confidence.

If someone were to claim that the phenomena said to be obstructive do not lead to obstruction when engaged in, I do not see anyone in the world — whether ascetic, brahmin, deva, Māra, Brahmā, or anyone else — who could rightly refute me. Not seeing this possibility, Sāriputta, I dwell having attained security, fearlessness, and confidence.

If someone were to claim that the Dhamma taught for the purpose of ending suffering does not lead the one who practices it rightly to the ending of suffering, I do not see anyone in the world — whether ascetic, brahmin, deva, Māra, Brahmā, or anyone else — who could rightly refute me. Not seeing this possibility, Sāriputta, I dwell having attained security, fearlessness, and confidence.

These, Sāriputta, are the four confidences of the Tathāgata. Endowed with these confidences, the Tathāgata claims the noble place, roars the lion's roar in assemblies, and sets in motion the spiritual teaching.

Sāriputta, when I know and see thus, should anyone say of me: 'The ascetic Gotama does not have any superhuman attributes or distinctions in wisdom and vision worthy of noble ones; the ascetic Gotama teaches a Dhamma hammered out by reasoning, conforming to a mode of investigation, and produced by his own intuition,' without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there. Just as, Sāriputta, a bhikkhu accomplished in virtue, collectedness, and wisdom would attain final knowledge in this very life, so, Sāriputta, I declare this: without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, he will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there.

Eight Assemblies

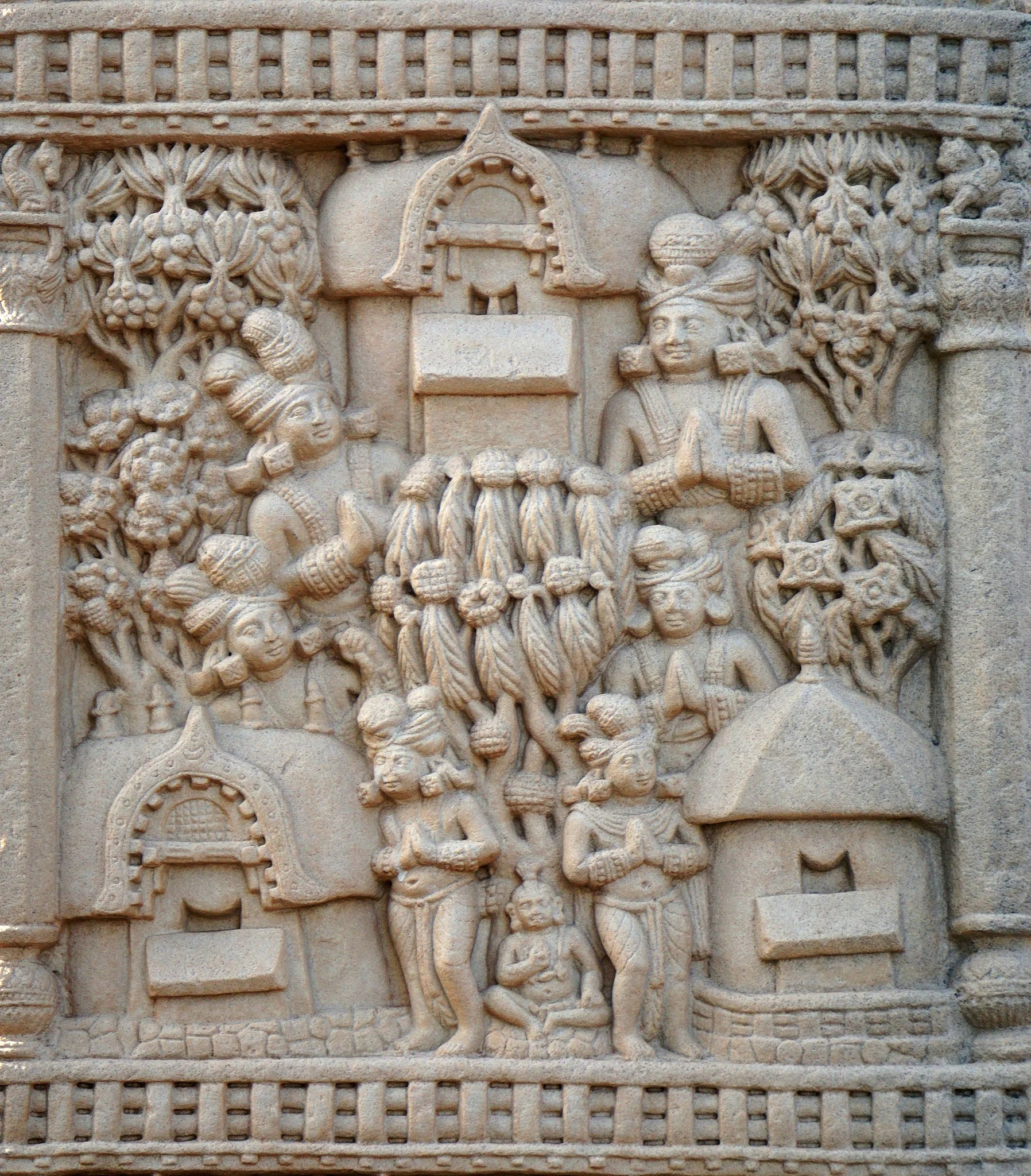

There are eight assemblies, Sāriputta. Which eight? The assembly of nobles, the assembly of brahmins, the assembly of householders, the assembly of ascetics, the assembly of the Four Great Kings, the assembly of the Thirty-Three Gods, the assembly of Māra, and the assembly of Brahmā — these, Sāriputta, are the eight assemblies. Endowed with these four confidences, the Tathāgata approaches and engages with these eight assemblies. I know, Sāriputta, that I have approached many hundreds of assemblies of nobles. There too, I have previously sat, conversed, and engaged in discussion. I do not see any indication, Sāriputta, that fear or timidity would descend upon me there. Not seeing this possibility, Sāriputta, I dwell having attained security, fearlessness, and confidence.

I know, Sāriputta, that I have approached many hundreds of assemblies of brahmins, householders, ascetics, the Four Great Kings, the Thirty-Three Gods, Māra, and Brahmā. There too, I have previously sat, conversed, and engaged in discussion. I do not see any indication, Sāriputta, that fear or timidity would descend upon me there. Not seeing this possibility, Sāriputta, I dwell having attained security, fearlessness, and confidence.

Sāriputta, when I know and see thus, should anyone say of me: 'The ascetic Gotama does not have any superhuman attributes or distinctions in wisdom and vision worthy of noble ones; the ascetic Gotama teaches a Dhamma hammered out by reasoning, conforming to a mode of investigation, and produced by his own intuition,' without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there. Just as, Sāriputta, a bhikkhu accomplished in virtue, collectedness, and wisdom would attain final knowledge in this very life, so, Sāriputta, I declare this: without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, he will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there.

Four Types of Birth

There are four types of births, Sāriputta. Which four? Egg-born, womb-born, moisture-born, and spontaneously-born.

And which, Sāriputta, is the egg-born birth? Those beings, Sāriputta, who are born breaking through an egg-shell — this, Sāriputta, is called the egg-born birth. And which, Sāriputta, is the womb-born birth? Those beings, Sāriputta, who are born breaking through a membrane — this, Sāriputta, is called the womb-born birth. And which, Sāriputta, is the moisture-born birth? Those beings, Sāriputta, who are born in putrid fish, or in a putrid corpse, or in putrid bean soup, or in a box, or in a cesspool — this, Sāriputta, is called the moisture-born birth. And which, Sāriputta, is the spontaneously-born birth? Gods, hell beings, some humans, and some beings in the lower realms — this, Sāriputta, is called the spontaneously-born birth. These, Sāriputta, are the four types of birth.

Sāriputta, when I know and see thus, should anyone say of me: 'The ascetic Gotama does not have any superhuman attributes or distinctions in wisdom and vision worthy of noble ones; the ascetic Gotama teaches a Dhamma hammered out by reasoning, conforming to a mode of investigation, and produced by his own intuition,' without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there. Just as, Sāriputta, a bhikkhu accomplished in virtue, collectedness, and wisdom would attain final knowledge in this very life, so, Sāriputta, I declare this: without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, he will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there.

Sāriputta, when I know and see thus, should anyone say of me: 'The ascetic Gotama does not have any superhuman attributes or distinctions in wisdom and vision worthy of noble ones; the ascetic Gotama teaches a Dhamma hammered out by reasoning, conforming to a mode of investigation, and produced by his own intuition,' without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there. Just as, Sāriputta, a bhikkhu accomplished in virtue, collectedness, and wisdom would attain final knowledge in this very life, so, Sāriputta, I declare this: without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, he will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there.

The Five Destinations and Nibbāna

There are five future destinations, Sāriputta. Which five? Hell, the animal realm, the realm of ghosts, human beings, and gods.

I know hell, Sāriputta, and the path to hell, and the practice that leads to hell; and how someone who practices that way, with the breaking up of the body, after death, arises in a state of loss, a bad destination, a plane of misery, in hell — I know that too. I know the animal realm, Sāriputta, and the path to the animal realm, and the practice that leads to the animal realm; and how someone who practices that way, with the breaking up of the body, after death, arises in the animal realm — I know that too. I know the realm of ghosts, Sāriputta, and the path to the realm of ghosts, and the practice that leads to the realm of ghosts; and how someone who practices that way, with the breaking up of the body, after death, arises in the realm of ghosts — I know that too. I know human beings, Sāriputta, and the path to the human world, and the practice that leads to the human world; and how someone who practices that way, with the breaking up of the body, after death, arises among humans — I know that too. I know the gods, Sāriputta, and the path to the world of gods, and the practice that leads to the world of gods; and how someone who practices that way, with the breaking up of the body, after death, arises in a good destination, a heavenly world — I know that too. I know Nibbāna, Sāriputta, and the path to Nibbāna, and the practice that leads to Nibbāna; and how someone who practices that way, with the exhaustion of the taints, attains in this very life the taintless liberation of mind and liberation by wisdom, having realized it with direct knowledge — I know that too.

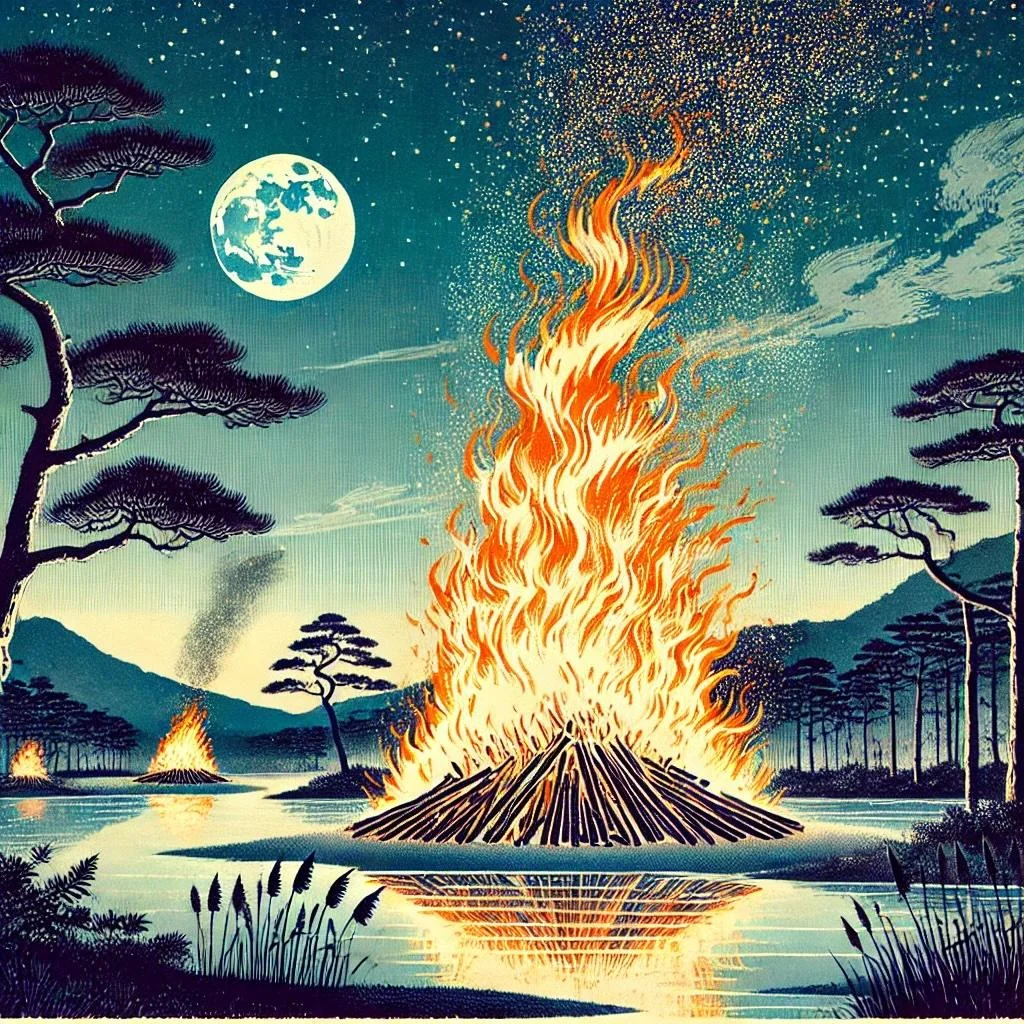

Here, Sāriputta, I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — thus, this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in a state of loss, in a bad destination, in a plane of misery, in hell. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in a state of loss, in a bad destination, in a plane of misery, in hell, experiencing intense, sharp, and painful feelings (sensations). Just as, Sāriputta, there is a pit of burning embers, more than a man's height, full of embers without flames, without smoke. Then, a person would come, scorched by the heat, overcome by heat, exhausted, thirsty, and parched, setting forth on that very direct path. Seeing him, a discerning person would say: 'This venerable person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that he will arrive at this very pit of embers.' At another time, the discerning person would see him fallen into that pit of embers, experiencing intense, sharp, and painful feelings (sensations).

Likewise, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in a state of loss, in a bad destination, in a plane of misery, in hell. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in a state of loss, in a bad destination, in a plane of misery, in hell, experiencing intense, sharp, and painful sensations.

Furthermore, here, Sāriputta, I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in the animal realm. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in the animal realm, experiencing intense, sharp, and painful sensations. Just as, Sāriputta, there is a cesspool greater than a man's height, full of excrement. Then, a person would come, scorched by heat, overcome by heat, exhausted, thirsty, and parched, setting forth on that very direct path. Seeing him, a discerning person would say: 'This venerable person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that he will arrive at this very cesspool.' At another time, the discerning person would see him fallen into that cesspool, experiencing intense, sharp, and painful sensations.

In the same way, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in the animal realm. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in the animal realm, experiencing intense, sharp, and painful sensations.

Furthermore, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in the realm of ghosts. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in the realm of ghosts, experiencing predominantly painful sensations. Just as, Sāriputta, there is a tree growing on uneven ground, with thin leaves and scanty shade. Then, a person would come, scorched by the heat, overcome by heat, exhausted, thirsty, and parched, setting forth on that very direct path. Seeing him, a discerning person would say: 'This venerable person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that he will arrive at this very tree.' At another time, the discerning person would see him sitting or lying down in the shade of that tree, experiencing predominantly painful sensations.

In the same way, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in the realm of ghosts. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in the realm of ghosts, experiencing predominantly painful sensations.

Here, Sāriputta, I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn among humans. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, among humans, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations. Just as, Sāriputta, there is a tree growing on even ground, with thick leaves and ample shade. Then, a person would come, scorched by the heat, overcome by heat, exhausted, thirsty, and parched, setting forth on that very direct path. Seeing him, a discerning person would say: 'This venerable person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that he will arrive at this very tree.' At another time, the discerning person would see him sitting or lying down in the shade of that tree, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations.

In the same way, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn among humans. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, among humans, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations.

Here, Sāriputta, I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind - 'This person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in a good destination, in a heavenly world.' I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in a good destination, in a heavenly world, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations. Just as, Sāriputta, there is a mansion, with a storied pavilion, plastered and painted, sheltered from the wind, with a fitted door and closed windows. Inside, there is a couch, spread with rugs, coverlets, and blankets, covered with a fine spread of kadali deer skins, with a canopy above and red pillows at both ends. Then, a person would come, scorched by heat, overcome by heat, exhausted, thirsty, and parched, setting forth on that very direct path. Seeing him, a discerning person would say: 'This venerable person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that he will arrive at this very mansion.' At another time, the discerning person would see him having entered that mansion, lying or sitting on that couch, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations.

In the same way, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the breaking up of the body, after death, he will be reborn in a good destination, in a heavenly world. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, reborn after the breaking up of the body, after death, in a good destination, in a heavenly world, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations.

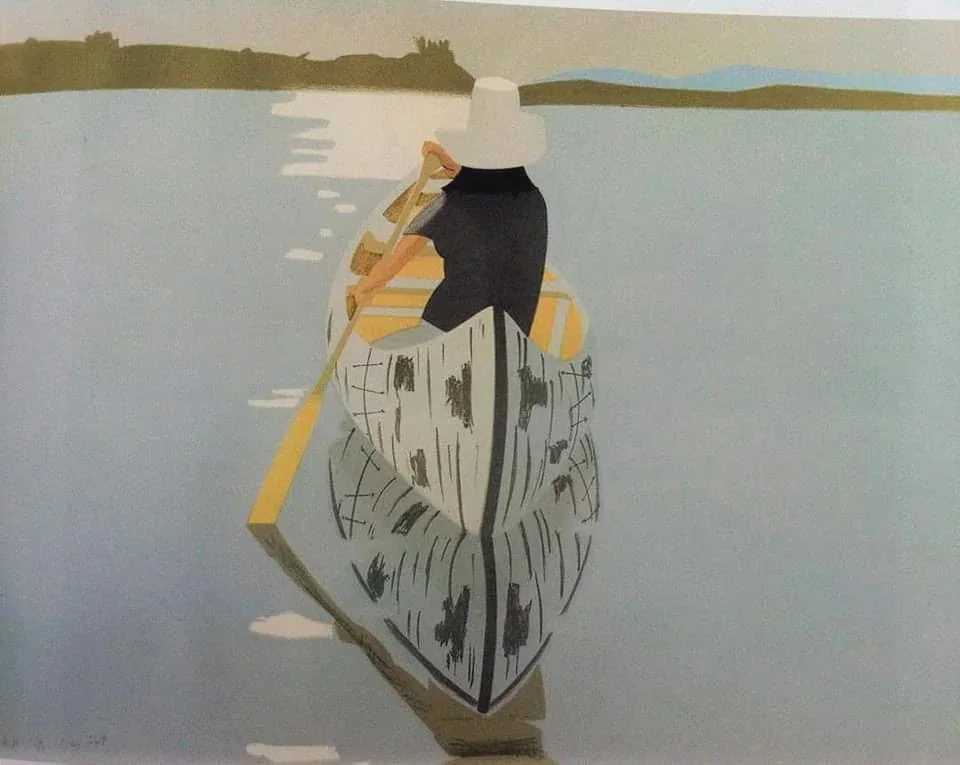

Here, Sāriputta, I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind — this person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the exhaustion of the taints, he will attain the undefiled liberation of mind and liberation by wisdom, having realized it with direct knowledge, in this visible state. I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, having realized the exhaustion of the taints, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations. Just as, Sāriputta, there is a pond with clear, cool, cold water, white and well-situated, delightful. Nearby is a dense grove. Then, a person would come, scorched by the heat, overcome by heat, exhausted, thirsty, and parched, setting forth on that very direct path. Seeing him, a discerning person would say: 'This venerable person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that he will arrive at this very pond.' At another time, the discerning person would see him having entered that pond, bathed, and drunk, having calmed all his heat and exhaustion, sitting or lying down in that grove, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations.

In the same way, Sāriputta, here I know a certain person by comprehending their mind with my mind - 'This person is practicing in such a way, behaving in such a way, and engaged in such a path that, with the exhaustion of the taints, he will attain the taintless liberation of mind and liberation by wisdom, having realized it with direct knowledge, in this visible state.' I see him at a later time with the divine eye, purified and surpassing human vision, having realized the exhaustion of the taints, experiencing predominantly pleasant sensations. These, Sāriputta, are the five destinations.

Sāriputta, when I know and see thus, should anyone say of me: 'The ascetic Gotama does not have any superhuman attributes or distinctions in wisdom and vision worthy of noble ones; the ascetic Gotama teaches a Dhamma hammered out by reasoning, conforming to a mode of investigation, and produced by his own intuition,' without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there. Just as, Sāriputta, a bhikkhu accomplished in virtue, collectedness, and wisdom would attain final knowledge in this very life, so, Sāriputta, I declare this: without abandoning that speech, without abandoning that mind, without relinquishing that view, he will be cast into hell just as he would be if physically carried there.

This discourse is preceded by the discourse on: The Ten Tathāgata Powers (From MN 12).

The discourse continues after this, you can read in full at https://suttacentral.net/mn12 ↗️.

This discourse is part of the collection of discourses in The Planes of Realization: From "In the Buddha's Words" by Bhikkhu Bodhi.